Westwind shared Annishinaabe teachings and traditional knowledge related to the symbolism of colours. Take a look here at the PowerPoint presentation she shared for more info and fantastic writing prompts.

Westwind shared Annishinaabe teachings and traditional knowledge related to the symbolism of colours. Take a look here at the PowerPoint presentation she shared for more info and fantastic writing prompts.

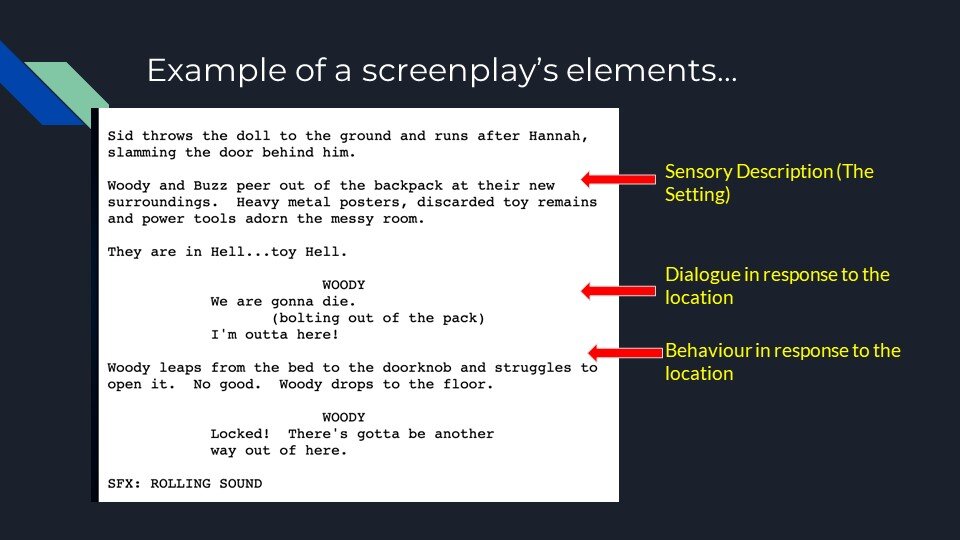

Watch this clip from the movie Toy Story (watch from 1:36 to 3:20) and remember that it started with words on the page:

Evoking Setting Using the Senses - Activity 1

Think about a couple of locations that might have a lot of physical obstacles.

Pick one of those and start to collect details about that location.

Describe that space in as much detail as you can including sights, sounds, smells, textures, and even tastes!

Think of every sensory detail you can for this location (sights, smells, sounds, tastes, textures) and describe each one. No detail is too small... the more specific the better.

e.g. there is a large brick wall with red bricks. One of the bricks is grey. The wall is cold to the touch.

React to your Scene! - Activity 2

Now place a character in this setting.

What do they say? How do they move?

When are they compelled to speak?

think of the Toy Story example

How do they move in response to the sensory elements in the room

e.g. the boy plugs his nose to avoid breathing in the smell of skunk.

In terms of formatting, you might like to try and make it look like the Toy Story example (see above)

Courier New Font/Capitalized Scene Heading

Start your paragraph with the Scene heading (e.g. EXT. A WIDE OPEN FIELD - DAY)

Try to write it in present tense (e.g. Doyle looks from Brand to Case, who is loading the beacon. Beyond him Doyle sees the mountain wave approaching)

Share your results below!

First, you may want to look at David’s fantastic PowerPoint presentation, which contains tons of useful info, tips, and tricks: https://youtu.be/h3iO0fLfTbs.

Writing Warm-Up

What was the last long conversation you had?

Can you remember any of exact sentences you spoke?

Can you remember any of the exact sentences that were spoken to you?

Write those down. Try for at least three. Don’t worry if you’re not getting them word for word.

Why do you think these sentences are memorable to you?

What Is a Character, Really?

Characters need agendas (wants)

Characters are revealed by what they say and what others say about them (they are not what the writer says about them)

But characters who talk about themselves are sometimes lying.

Characters Agendas

For our first exercise, let’s consider this idea that characters who talk about themselves are sometimes not telling the truth.

What are some situations where a person would speak about themselves but not be entirely truthful

(Write down as many as you can - 5 mins)

What reason would someone have to talk about themselves and embellish facts?

What purpose would the tactic of lying serve?

Note that this doesn’t need to be harmful. i.e. are there justified instances of characters withholding truth?

Prompt #1: Chose one of the scenarios you’ve just come up with and using dialogue only, have your character tell an untruthful story about themselves which serves their agenda.

Prompt #2: Tell the Truth with Dialogue

Now take that exact same character and have them confess that the story they have told is not the truth.

What do they say?

Why are they admitting the lie?

How do they feel about ‘coming clean’ here?

Don’t stop. Don’t censor. Remember, you can only use speech here.

10-15 minutes.

This workshop is a continuation of the theme of “My Personal Creation Story,” with a focus on our life purpose on Mother Earth:

I recap the last workshop about I, as a Spirit Being in the Spirit World, who sat on a rock overlooking an ocean and having a conversation with Gichi Manitou (Creator) who asks me, “What are you going to do with your life?” And as we converse, I tell Gichi Manitou how I want to spend my life on Mother Earth. And then it takes me 9 moons to travel from the Spirit World to Mother Earth.

I speak about the Bundle that I carried with me on my journey to Mother Earth. Anishanaabek call this a Medicine Bundle. This can be an object or an idea. Essentially, it refers to the talents or inherent gifts we have been given to facilitate our life purpose. I want to impress on the writers that this is not affiliated with any particular spiritual practice or belief, that this Bundle can be an idea that can be interpreted as a passion, talent or gift we inherently possess.

As an example, I shared what is in my personal Medicine Bundle, that I have objects that I keep: One item is my late grandson’s red plaid shirt because he taught me how to nurture my spirit child because I didn’t have the opportunity to actually be a child during my childhood. He taught me as his grandmother, that I can also be a kid. He taught me how to play and imagine like a sacred child. I added that his shirt also helps me get through times of grief and loss.

WRITING PROMPT: What is in your medicine bundle?

RESOURCES:

Medicine Walk, Richard Wagamese (author)

The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway, Eddie Benton-Banai (Chief, Three Fires Society)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sHyRXCG_c28, an interesting example of a Medicine Bundle that has been adapted to personal preference.

We started today’s workshop with a short free write prompt: Write about a place, person, or object that is “home” to you. Try to capture as many of the five senses as possible in your description: sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touch/textures.

Next, we read part of a wonderful short essay by our own instructor and collective member, Leonarda Carranza, called Tongues.

Some questions you may wish to consider about the piece (feel free to post your response in the space below):

◦ Do you relate to the narrator’s journey in this piece? Why or why not?

◦ Why do you think Leonarda chose to write this piece using second person – “you”? Did you find that this was an effective choice?

◦ The feminist movement in the 60s and 70s brought us the slogan, “The personal is political.” How does Leonarda incorporate history and social justice issues into a very personal story? Was this effective for you?

Writing Exercise: Revision

Go back to your free write piece and see if there’s anything you can change or add to it, for example:

◦ Try writing the piece using either direct address (speaking directly to the object/place/person, calling them “you”) or second person (referring to yourself as “you”)

◦ Try making the personal political. What social or historical context can you add to your piece?

If you prefer, you can write a new piece that incorporates one of these elements instead.

Writing Exercise: Languages

◦ What is your native language? Is it different from your parents’ or grandparents’ native language? Remember that your/their native language might be a dialect, like joual (working-class Quebecois French) or Standard Black English (or, in my case, South African English). Write a scene in which you try to convey some of the complications that you feel about writing and communicating in English or in your native tongue: the difficulties, joys, connections, and ruptures.

OR

◦ Have you ever tried to learn another language? Ever used that language to talk with a native speaker? Write about the experience(s) in a way that captures the joy, pain, embarrassment, humour, etc. of learning languages.

Liz shared a poem of her own called “A Wake,” from her award-winning collection Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent.

Writing Exercise

1.Think about a time when you had an experience of wonder, awe, or curiosity (i.e., fog rolling in looking like smoke off of lake Superior). Something that gave you pause, made you question or reflect. Something breathtaking or quizzical/strange.

2.Tie that experience to a particular location, landscape. If possible bring the psychological experience of awe/questioning into the poem.

3.Choose a line or image to repeat at least once.

4.Spend 15 minutes writing reflectively using these prompts.

Check out Liz’s PowerPoint presentation here and try out these writing prompts:

Writing Exercise #1

1.Choose a landscape or location that has resonated strongly with you at a specific time in your life (i.e., being 19 years old along a prairie highway in Manitoba)

2.“Triage” that landscape. Identify all the sensory details (Sight, smell, touch, sound, etc) associated with that place.

3.What are the emotions connected with those details? What do they make you think of now?

4.Spend 10 minutes writing reflectively using these prompts. You can choose to write in the form of a poem or prose. Whichever works best for you.

Writing Exercise #2

•Consider the place you are currently in (room, house, street, etc)

•What if the wild intervened in some way (i.e., “the light step of a cougar”)? What would that encounter look like?

•How would the presence of a wild being make you experience your current space in a new way? (i.e., find myself again / in a new place)

•Again, considering these prompts, compose a short poem/paragraph (5-10 minutes)

Take a look at the slides from this awesome workshop for everything David shared: https://youtu.be/miRkF08AXDM. Or you can read the summary below. Be sure to post your writing in the comment section!

Imagining the Future of the Familiar

Scene from Upload (2020)

Note how many everyday objects are re-imagined in this scene.

This includes biological, technological, and spiritual

“Little Thing” (Short Film) (2018)

Note the effect of an inhuman character viewing the familiar human world through their lens.

Exercise 1: Re-imagining the Familiar

List a series of common, everyday objects, places, or events.

For those who were part of this workshop in May, you may wish to try the events or places prompt

e.g., What does a wedding of the future look like? (Event)

e.g., What does a classroom of the future look like? (Place)

Now let’s imagine how they will be different in 50 years (there are no wrong answers).

Pick two or three from your list and speculate on how they will be different

Will they be made of different materials? Will how we use them change? Will they be as common? Obsolete? Will they have a different use?

Exercise 2:

In all writing, your reader is being dropped into your world.

Some of you will have done “the Fish out of Water” exercise where a character finding their bearings in a new world is exactly what your reader experiences.

In your world of the future, what are the three things your “fish out of water” notices first?

The topic of today’s workshop was Superstition.

We started with some examples shared from a recent project by Australian artist Vipoo Srivilasa in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The artist asked people from around the world to share their designs for a COVID-19 Deity to protect them during the pandemic. Out of 63 submissions, the 19 most inspiring deities were chosen by the artist, who will now turn them into ceramic sculptures. You can take a look at these 19 deities here.

Go ahead, try it yourself! You may want to start by thinking about what has been the most difficult adjustment for you to make since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. What losses have you had to accept or get used to? What problems have gotten worse? Now think of a being who has the power to make that problem go away. Perhaps your deity’s ability comes from a superpower, or a special weapon—maybe even one that’s specific to your culture or to your own personal history.

Start by drawing your deity. Next, tell us about your deity and their ability to fight COVID-19 and promote wellness wherever they go!

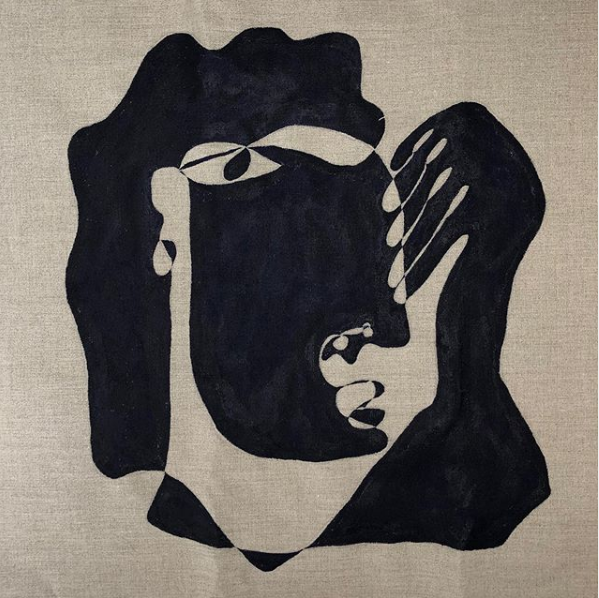

This deity was shared by one of our participants:

Next, try this writing prompt:

Your deity is taking a well-deserved day off from fighting the novel coronavirus and has decided to take the elevator to the top of the CN Tower to enjoy the view. Suddenly, power goes out across downtown Toronto and they’re stuck at the top of the tower. Their cell phone starts to ring. They answer it, and hear…

Finally, here’s a prompt related to the topic of superstition more generally:

Write a story about a superstition that you believe in OR write about a superstition that your ancestors may have believed in.

On Wednesday, September 23rd, one of our newest instructors, Westwind Evening, led a session featuring Indigenous Turtle Island stories. She shared a short version of the Anishnaabe Creation story to set up the following prompt:

What is the conversation that took place when you were a spirit being sitting on a rock overlooking a calm ocean with Gitche Manitou (Creator) deliberating on what life journey you create for yourself on Mother Earth?

Today, we talked about a short essay by the contemporary American writer Charles D’Ambrosio.

Here’s a link to the essay: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2004/06/14/train-in-vain

And here’s me talking about it: https://youtu.be/6RoVvARBgBI

Writing Exercise #1

Imagine that you have lived to be 108 years old. You’re extremely grumpy, particularly about the one thing you dislike that young people these days seem to love. In fact, you’ve decided to start a social movement in which you will try to have this thing abolished. Write a speech to persuade other people that they should join your movement. For example, you might call your speech Against Flowers, Against Happiness, or Against Going to the Beach.

Writing Exercise #2

Write about a holiday you took, either as a child or an adult, where something went very wrong OR write about a tense family occasion or event.

This week, we discussed writing a poem ‘after’ another poet — these poems can also be called response poems. They are often written ‘in homage to’ or ‘inspired by’ another poem. They can take a wide variety of forms.

We considered the following definitions of ‘after’ poems as well as the controversies they can bring about when it comes to plagiarism to guide us through the session.

1) “When you write a poem heavily influenced by another poem you always acknowledge it with the word ‘after’ and the original poet’s name. Poets are often inspired by stories: legends, fairy tales, religious narratives, myth and other poems.”

(https://poetrysociety.org.uk/competitions/foyle-young-poets-of-the-year-award/foyle-lesson-plans/once-upon-a-poem/)

2) “When writing a poem after another writer’s work, create something that reacts to their work or emulates (but doesn’t copy) their style. You’re aiming to create something that can continue a conversation about their work.”

(https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-fiction/how-to-draw-influence-from-other-writers-without-plagiarizing-6-tips-to-avoid-an-ailey-otoole-situation#:~:text=When%20writing%20a%20poem%20after,feel%20honored%20rather%20than%20cheated.)

3) “Cortese isn’t the only small-press poet wondering out loud or online whether ‘after’ poems — which can connote anything from ‘in homage to’ or ‘in conversation with’ to ‘in the style of’ or ‘inspired by’ — are sometimes used as cover for laziness or even outright theft… There’s nothing straightforward about the debate, and nothing particularly new about the ‘after’ convention. Poetry is a medium in which sampling, allusion, and conversation have always been part of the game… The best solution might be for poets to assume ignorance before malice, and to ask questions before making accusations. But it also behooves writers intent on entering into dialogue with other poets on the page to start by doing so IRL — to practice an aesthetic version of affirmative consent. ‘You might want to find out,’ says Orr, ‘whether they want that conversation to take place, whether they’re open to it — because they don’t have to be.’”

(https://www.vulture.com/2018/12/poetry-twitter-debates-whether-after-poems-are-plagiarism.html)

The poem we read this week was an excerpt from Dionne Brand’s thirsty, published in 2002. Read the excerpt here and listen to the poet reading the excerpt here before moving on to the writing exercises.

Here’s a snippet of the poem to spark your curiosity:

This city is beauty

unbreakable and amorous as eyelids,

in the streets, pressed with fierce departures,

submerged landings,

I am innocent as thresholds

and smashed night birds, lovesick,

as empty elevators

let me declare doorways,

corners, pursuit, let me say

standing here in eyelashes, in

invisible breasts, in the shrinking lake

in the tiny shops of untrue recollections,

the brittle, gnawed life we live,

I am held, and held

Copyright © Dionne Brand, 2002. From poetryinvoice.com.

Writing Exercise #1:

Write a poem after Dionne Brand’s excerpt from thirsty. Use the line “This city is…” to begin your poem. Choose one more line from the poem and use it somewhere else in your poem (at the beginning, the end, hidden in one of the stanzas, anywhere you’d like).

Writing Exercise #2:

Write a different poem after Dionne Brand’s excerpt from thirsty. Use the line “would I have had a different life” as a prompt to begin your poem.

There were some beautiful poems shared in the workshop. Whether or not you were present for the live session, share your poems in the comments below!

This week, we discussed the roles of audience, speaker, and poet. In particular, we focused on the myth of a ‘neutral’ audience.

When we talk about poetry, what do we mean when we say ‘audience’?

“An Audience is the person for whom a writer writes, or composer composes. A writer uses a particular style of language, tone, and content according to what [they] know about [their] audience. In simple words, audience refers to the spectators, listeners, and intended readers of a writing, performance, or speech” (https://literarydevices.net/audience/).

On audience and neutrality

When we think of an audience for our poetry, who are we talking about? We can mean this in two senses of the word: the audience as reader and the audience as listener (the person listening to the speaker tell their story).

”One of the central principles of feminist criticism is that no account can ever be neutral.”

Sexual/Textual Politics, Toril Moi (1985)

“That’s one thing I decided about audience a long time ago. That the audience would simply have to walk in if they could and if they couldn’t, well, they could go read something else.”

Dionne Brand, as quoted in The Black Atlantic Reconsidered: Black Canadian Writing, Cultural History, and the Presence of the Past, Winfried Siemerling (2015)

“The idea that poetry is not just about aesthetic enjoyment but about constructing the identities of poets and audiences, performing social relationships, and establishing public communities of critics is profound.”

The Cultural Politics of Slam Poetry: Race, Identity, and the Performance of Popular Verse in America, Susan B. A. Somers-Willett (2009)

Audience in your own poetry

How do you imagine your audience? What do they look like? What language do they speak? How old are they?

What is a ‘neutral’ audience? As a culture, we may have been told, explicitly or implicitly, that a neutral audience might be White, English-speaking, neurotypical, abled, heterosexual, cisgender.

Can we subvert this? Can we flip it on its head?

As poets, we are given the job of witness. We are witnessing this moment. Who do we write for? Whom do we tell what we are seeing?

Reading living poets

“There Are Birds Here” by Jamaal May. Here is the poem. Here is a video of the poet reading the poem.

Think about who the audience for this poem might be. Who is the poet writing for? Who is the speaker of this poem speaking to?

Further reading:

“Dinosaurs in the Hood” by Danez Smith. Here is the poem. Here is a video of the poet reading the poem.

“From thirsty” by Dionne Brand. Here is the poem. Here is a video of the poet reading the poem.

Consider who the audience for these poems might be. Who is the poet writing for? Who is the speaker of this poem speaking to?

Writing Exercise #1:

Imagine your audience is you, in all your intersections. Write a poem to yourself, an imagined version of yourself, or someone just like you. Talk to them. Tell them what is happening, what you are seeing, feeling, and experiencing in this moment.

Writing Exercise #2:

Write a poem for someone you know. Choose someone specific in your mind. Write to them. Talk to them. Tell them what is happening, what you are seeing, feeling, and experiencing in this moment.

Closing thoughts

What will we do with the language we have been given? With the gift of these poems? Take care of yourselves. Read poetry, read living poets, read Black and Indigenous poets. Witness where and when we are. Write from your own particular position. Write to your own audience. Tell them what you see. Keep writing.

We started out today talking about Pride month, the origins of Pride as a riot against the police led by queer and trans Black women, and the Black Lives Matters movement today. We were reminded that June is also Indigenous History Month.

And then we began to talk about monsters: Frankenstein, Cookie Monster, golems, the Loch Ness Monster, the novel coronavirus.

Brainstorming Exercise

Take a few minutes to write about a monster from your religion or culture. Record everything you know about this creature.

OR

Invent a monster. What does your monster want? Does it have fears? How about any secrets?

Post about your monster in the comment section below!

Reading

We read and discussed an excerpt from the story “Greedy Choke Puppy” by the amazing sci-fi/fantasy writer, Nalo Hopkinson. This beautifully written story, from a collection called Skin Folk, is about a soucouyant, a vampire-like creature from West Indian folklore. It contains several genuinely surprising twists.

How to Create Scenes that Twist and Turn

The following is a summary of some of Robert McKee’s ideas from his well-known screenwriting guide, Story:

•According to McKee, scenes should be built around desire, action, conflict, and change

•A scene begins with a problem or goal that’s based on some value at stake in your character’s life, such as justice, freedom, love, truth, etc.

•In order to sizzle, every scene should turn, either from positive to negative, or from negative to positive

•McKee continues that writers should try “to crack open the gap between expectation and result”

•The effects of such turning points include surprise, increased curiosity, and insight on the part of readers

Writing Exercise

Try it yourself!

Write a story about someone who realizes they’re married to the monster you brainstormed about in the first exercise. See if you can give the monster’s spouse a secret of their own to reveal!

Be sure to comment below!

In today’s workshop, we identified and played with a few conventions of romance writing:

1. Romance is the meat and potatoes

· Your story should center on the growing relationship between your main characters. While it may include other elements (i.e. mystery, fantasy), the main focus should be moving this relationship towards an emotionally satisfying ending (whatever that looks like to you!)

2. You need obstacles!

· To keep your readers hooked, your characters should face challenges to their "happily ever after." These may include love triangles, secrets, external complications or personal traits that complicate things.

3. Integrate intimacy rituals

· These might be inside jokes, shared traditions, meaningful gestures, private languages -- things that only they do together. The way these rituals change show growth in your characters - because to fall in love requires self-reflection.

Most importantly, your interpretation of romance should be unique to your characters!

Most romantic relationships begin with a memorable meeting!

SPARK - A classic meet-cute with an instant attraction!

OR

SNARK - It's not love at first sight - but that doesn't mean there's no emotion there!

Prompt: Start a scene with “We were the only two people who took the words “costume party” seriously.” Think about how your characters’ personalities can be expressed through concrete details.

Another convention of romance as a genre is the use of adaptations (retellings of classic stories – with a twist!). Adaptation allow us to:

- Play with tropes of the genre

- Write in characters who have been traditionally excluded

- Create twists on classic characters and storylines

- Engage with old and new audiences!

Reading: Excerpt from Ayesha at Last, by Uzma Jalaluddin - modern retelling of Pride & Prejudice

https://ew.com/books/2018/11/14/ayesha-at-last-first-look-uzma-jalaluddin/

He wondered if he would see her today. Khalid Mirza sat at the breakfast bar of his light-filled kitchen, long legs almost reaching the floor. It was seven in the morning, and his eyes were trained on the window, the one with the best view of the townhouse complex across the street.

His patience was rewarded.

A young woman wearing a purple hijab, blue button-down shirt, blazer and black pants ran down the steps of the middle townhouse, balancing a red ceramic travel mug and canvas satchel. She stumbled but caught herself, skidding to a stop in front of an aging sedan. She put the mug on the hood of the car and unlocked the door.

Khalid had seen her several times since he had moved into the neighbourhood two months ago, always with her red ceramic mug, always in a hurry. She was a petite woman with a round face and dreamy smile, skin a golden burnished copper that glowed in the sullen March morning.

It is not appropriate to stare at women, no matter how interesting their purple hijabs, Khalid reminded himself.

Yet his eyes returned for a second, wistful look. She was so beautiful.

The sound of Bollywood music blaring from a car speaker made the young woman freeze. She peered around her Toyota Corolla to see a red Mercedes SLK convertible zoom into her driveway. Khalid watched as the young woman dropped to a crouch behind her car. Who was she hiding from? He leaned forward for a better look.

“What are you looking at, Khalid?” asked his mother, Farzana. “Nothing, Ammi,” Khalid said, and took a bite of the clammy scrambled eggs Farzana had prepared for breakfast. When he looked up again, the young woman and her canvas satchel were inside the Toyota.

Her red travel mug was not.

It flew off the roof of her car as she sped away, smashing into a hundred pieces and narrowly missing the red Mercedes.

Khalid laughed out loud. When he looked up, he caught his mother’s stern gaze.

“It’s such a lovely day outside,” Farzana said, giving her son a hard look. “I can see why your eyes are drawn to the view.”

Khalid flushed at her words. Ammi had been dropping hints lately. She thought it was time for him to marry. He had a steady job, and twenty-six was a good age to settle down. Their family was wealthy and could easily pay for the large wedding his mother wanted.

“I was going to tell you after I’d made a few choices, but it appears you are ready to hear the news. I have begun the search for your wife,” Farzana announced, and her tone brooked no opposition. “Love comes after marriage, not before.”

Prompt: Write a short "adaptation" of a love story using a modern form of communication!

A few examples:

• A declaration of romance left on a voicemail

• A love story foretold in a character's horoscope

• A love story told through a Kijiji ad

• A love story told in a Tweet (280 characters or less!)

• A first date recapped in an Ask Me Anything post

• A love story told through an advice column

• The story of a wedding told through a Yelp review (with a rating!)

• A declaration of love delivered over text (with emojis)

Please share your memorable meetings and adaptations in the comments section below!

You can also check out the PowerPoint video for the workshop here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCPdmSPhhRs&feature=youtu.be

World Building for Science Fiction/Speculative Fiction

This week we looked at science fiction and speculative fiction writing, not just as style, but as ways of freeing up your creative process. The overall goal was world building, but the two main points that we explored this week are as follows:

Science fiction is about ideas and “What If?” questions.

Science fiction allows you to free yourself from the “need to be right” when creating your stories, characters, and settings.

This type of writing can apply to any genre you write in. We’ve probably seen many examples from film (Back the Future 2) and television (Black Mirror), but these techniques will also apply to Fiction (see this excerpt from Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles); Poetry (see Sarah Lindsay’s Valhalla Burn Unit on the Moon Callisto); and even writing for the stage.

The Language of Science Fiction Science fiction is often concerned with the future, and as such, writers are given free reign to create worlds as extensions of our own. This gives us the chance to speculate on the future of familiar biological, social, technological, and psychological circumstances.

Exercise 1: Re-imagine the Familiar

List a series of common, everyday objects or systems. Even ones in your immediate surroundings.

Pick two or three from your list and speculate on how they will be different 50 years from today.

Will they be made of different materials? Will how we use them change? Will they be as common? Obsolete? Will they have a different use?

This is often the first step in creating new worlds for our readers. Think about how the ‘everyday’ becomes new in science fiction/fantasy: the toy top in Inception, the notion of school in the Harry Potter series, romantic love in The Shape of Water.

From this initial exercise, we can start filling in the world around the objects and systems you re-imagined by evoking the entire sensory experience around the object itself. Here’s that exercise.

Exercise 2: Sci-Fi & Fantasy World Building (Outline)

Using Exercise 1 as a springboard, use the Five Senses to make familiar things strange in your futuristic world. There are no wrong answers. Science fiction is often used synonymously with the term Speculative Fiction as the writer is speculating on a future. Release the need to be “right”

What Year is it? ____________________________

Where are we? _______________________________

What do you see?

the buildings, the sky, the modes of transportation. Is there vegetation? Are there animals? Who lives here and what do they look like? Do you know why the world is the way it is? (note: you don’t need to.)

What do you hear?

the sounds/silences of traffic, the sounds/silences of the landscape, the voices of residents (if any), the sounds/silences of technology

What materials do you feel?

what are the buildings made of? What are the streets made of? What materials are used for clothing? Does your world contain human-made elements or is it more nature-based?

What do you smell/taste?

what does the air smell like? Is it good? Bad? What other smells are present based on your answers above? What is the source of the air quality?

Bringing it Together: In a descriptive paragraph. bring the answers to your questionnaire above together to introduce us to the sensory experience of this brave new world. Feel free to share your paragraph in the comments!

For more, check out this fantastic slide presentation. Use the comments section below to share your writing!

This week, we’re trying out ekphrastic poetry.

Ekphrasis comes from ‘description’ in Greek. Ekphrastic poems are poems that respond to works of visual art (paintings, photographs, sculptures). According to the Poetry Foundation, “an ekphrastic poem is a vivid description of a scene or, more commonly, a work of art.”

Modern ekphrastic poems have let go of the elaborate description used by poets when writing the form in Ancient Greece (think: Homer’s Iliad). Instead, they try to “interpret, inhabit, confront, and speak to their subjects.”

The poet narrates, reflects, amplifies, and expands the meaning or ‘action’ in the work of art they’re writing about. Learn more about ekphrastic poems here.

Here’s an ekphrastic poem by W.H. Auden written in response to Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1558). And here’s another by William Carlos Williams responding to the same painting.

In the February 2017 issue of Poetry, Kathleen Rooney responds to René Magritte’s Le tombeau des lutteurs (The tomb of the wrestlers) (1960) below:

“Le Tombeau des Lutteurs”

by Kathleen Rooney (2017)

It is a tragedy, yes, but a confusing one. What happened to the wrestlers and / where have they gone? Loulou the Pomeranian would love to know. / Outdoors the hills are buried in snow, but inside a rose, a rose full-blown, a / roomful of rose. The bloom and its shadow overtaking the space. The bloom / proposing an impossible tomb.

Read Kathleen’s full poem here.

Our task is this:

Find pieces of visual art (illustration, painting, photography, sculpture, etc.) that you enjoy or that interest you. Look for them on Instagram, Google, magazines, anywhere you like. Write a poem responding to the work of art you found. Use freewriting (i.e. writing without stopping or editing for a timed period). Don’t censor yourself. Use line breaks, punctuation, and spacing at your leisure.

Here are a few pieces to help get you started:

Instagram: @sploooring

Instagram: @maggiecoledraws

Instagram: Hamza Lafrouji

Instagram: @ija_monet

Instagram: @christianespangsberg

Share your ekphrastic poems below!

Today, we’re talking about tastes and smells and how they can conjure up a strong sense of place or of a particular person (lavender always makes me think of my grandmother because she used to sew potpourri holders and put lavender inside). Tastes and smells can also make us think of our culture and of our childhood. All of these elements make for fantastic memoir writing.

First, make a list of your 10 favourite smells. Some of my favourites include the top of my cat’s head, the smell of garlic roasting, an orange being peeled, bread baking, or of laundry steam being vented from inside a building. Note that you can also do this exercise with smells you dislike: the smell of burnt hair and the smell of frying bacon would be on my list for sure.

Next, choose three of your favourite smells and jot down a few memories associated with each of them. Write down any other sensory details (taste, sound, sight, touch) you remember as well. Including these details in memoir is what really makes a piece of writing come alive for the reader.

Finally, choose one of these memories and write about it. See if you can evoke a sense of the place where the scene took place and/or an important person in your life through focusing on these sensory details. Share your writing in the comments section.

Sometimes, choosing a specific form for a piece of memoir helps us get the memories down on paper. This is especially true of difficult or even traumatic memories. This type of essay is sometimes called a “hermit crab essay” because, like a hermit crab who borrows a shell for another animal, these forms provide a pre-made structure that can house our writing.

Here is an excerpt from a hermit-crab short-story called “A Recipe for Disaster” by Eufemia Fantetti (reprinted with kind permission from the author). The story is from her award-winning short-story collection of the same name:

A Recipe for Disaster, Eufemia Fantetti

PREP TIME: Imprecise

COOK TIME: In Season

YIELD: Serves 2

Meet someone you are ¼ compatible with. Base this compatibility ½ on the fact that you are carbon-based life forms and ½ on your sad pasts.

Eve possesses limited skills in the kitchen. She knows the quote about how simple it is to keep a man as long as one is a maid in the living room, a cook in the kitchen and a whore in the bedroom. She has no gusto for any of these roles.

Throughout Eve’s childhood, she sustained an endless series of pinches, a tight squeezing of a cheek or forearm skin with the ever-present question, “You eating enough?”

When Eve’s father left Italy, it was a poverty-stricken country recovering from political turmoil; a post-Second World War classroom photo shows his eyes bigger than his stomach, the small organ shrunken from malnutrition. Now the cost of a cappuccino is ridiculous in both countries and everyone loves Italian cuisine.

“Never forget,” says her father, as he roams the aisles of cheap produce at No Frills, “Canada best country for the food.”

Eve has met someone. His name is Adam. Their friends this funny, and fortuitous.

*

Spend some time straining through failed relationships, measure each sordid detail together.

Adam’s family has also come from famine. “Everyone did.” He shrugs when Eve points this out. They are children of different diasporas, born after the mass exodus, each searching for small comforts in the form of food, hungry for a home. His family also lost their religion, switching from Catholic to Protestant generations ago, simply to survive. Eve’s family thinks the road to hell is paved with Protestants.

Adam and Eve are both atheists, him more so than her. Eve would like to believe in something—even if it’s only in the healing power of food: the redemption found in every morsel, every meal.

Try it yourself! Tell a story (fiction or non-fiction) using the form of a recipe. Share your writing in the comments below!

Our characters reveal themselves by how the speak and how they behave. With that in mind, this workshop focused on how to get your characters talking in consistent but unique ways.

First, a few terms simplified.

Dialogue - the speech of people in your story. The words they speak out loud.

e.g. Birdman (2014)

Monologue - when only one character speaks.

e.g. Selah and the Spades (2020)

Tactics - the things characters say or do to get what they want and need.

The Four Layers of Character

Adapted from The Playwright’s Guidebook by Stuart Spencer

1. General Qualities

The starting points for character, but not character itself. These are the general truths about a person (e.g. good, evil, nice, mean)

2. Emotions

This is how a character feels at any given moment in your story. Emotions are motivated by the general qualities of your character (e.g. a kind character might feel empathy)

Note: we get what is called a Complex Character when emotional states seem to contradict the general qualities of a character. For example, a “kind” character who doesn’t feel empathy, or a “mean” character who feels charitable.

3. Action

Action is what a character wants. It arises from their general qualities and emotions and motivates all speech and behaviour.

4. Speech/Behaviour

What your character says and does in the pursuit of their desire. This is how characters are revealed.

Character Building Exercise

1. Write out 5 general qualities for characters

2. For each of these general qualities, attach an emotion to them

3. Given your general quality-emotion pairs, create an action. What might someone with each combination you’ve created want or desire?

4. You now have now laid the foundation for 5 potential characters. Which one of these combinations most intrigues you? You will now take the character into the monologue exercise and get them speaking.

Write a Monologue

Prompt: Your character wants to leave a party they are at.

· Using dialogue only (the character’s voice) and given their general quality, what do they say? Who are they speaking to?

· Keeping in mind the general quality, how do they feel and what are they saying to justify leaving this party (what details are they reacting to?)

· One restriction: they can’t leave this party in this monologue!

· Don’t stop. Don’t censor. 15 minutes.

Potential Follow-Up: Bring one of your other characters from the Character Building Exercise into the party. What if they don’t want your original character to leave the party? What do they say? How do they behave given their general quality?

In this Wednesday’s workshop, we played with the idea of “constraints” — what happens when we apply restrictions or rules that require the poet to move their focus from image and metaphor to something as specific as counting syllables?

In order to play with formal constraints and short forms, we explored the Japanese forms of Haiku and Tanka.

Haiku (俳句) is a short form of Japanese poetry. Traditional haiku often consist of 17 on (loosely translated as “syllables”), in three lines divided like so: 5 - 7 - 5.

Tanka is a slightly longer short form consisting of five lines usually with the following pattern of on (or number of syllables per line): 5 - 7 - 5 - 7 - 7.

A syllable is a part of a word pronounced as a unit. It is usually made up of a vowel alone or a vowel with one or more consonants. For example, the word “haiku” has two syllables: Hai (1) - ku (2); the word “traditional” has four syllables: tra (1) - di (2) - tion (3) - al (4).

The essence of haiku is kiru, or “splitting.” This is often represented by the juxtaposition of two images or ideas and a kireji (a “splitting word”) or a punctuation mark (i.e. “;” or “—”) between them.

A haiku also typically contains a kigo (or a “season word”), usually drawn from a saijiki, an extensive but defined list of such terms. Often focusing on images from nature, haiku emphasizes simplicity, intensity, and directness of expression.

“The light of a candle” is a Haiku written by Yosa Buson, one of the three classical masters of the form. This video provides a sampling of haiku read in the original Japanese verse, with English translations provided.

Haiku Writing Exercises

1. Write as many haiku stanzas following the 5 / 7 / 5 structure as you can in 10 minutes.

2. For an added constraint, try to incorporate the kiru: the juxtaposition of two images or ideas. To mark the juxtaposition, use a kireji (or “cutting word”) or a punctuation mark (“;” or “—”).

3. For another added constraint, use a kigo (or “season word”) in your poem. Here are a few for spring:

new, warm, serene, fog, rain, haze, thin ice, soil, seed, frog, silkworm, butterfly, blossom, willow, dandelion, primrose, daisy

Tanka Background

Like the sonnet, the tanka employs a turn, or pivotal image, which marks the transition from the examination of an image to the examination of the personal response. This turn is located within the third line, connecting the kami-no-ku, or upper poem, with the shimo-no-ku, or lower poem.

“Person of the Playful Star” is a tanka written by Tada Chimako.

Tanka Wring Exercises

1. Write a tanka following the 5 / 7 / 5 / 7 / 7 structure.

2. For an added constraint, try to include a “turn” or pivotal image in the third line of your poem, connecting the kami-no-ku, or upper poem, with the shimo-no-ku, or lower poem.

Please share your own haikus and tankas in the comments section below!

Check out the PowerPoint video for the workshop here: